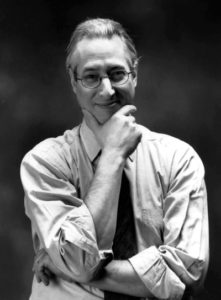

The Author Joshua M. Greene

Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison

Joshua Greene sits at his desk, cluttered with textbooks, manuscripts, videos and notes. From all appearances he could be a teacher, author, filmmaker or lecturer. In truth, he is all of the above. And truth is the operative word for this seeker.

Best known for his award-winning books on the Holocaust, including Justice at Dachau: The Trials of an American Prosecutor and Witness: Voices from the Holocaust, he has also produced acclaimed documentaries for PBS and the Disney Channel—more than 50 productions tracing journeys to enlightenment. And those journeys have had an impact on their chronicler.

Greene’s attraction to Holocaust studies was personal. “I grew up in the 1960s. In my circles, there was a lot of talk about yoga and peace but no one was talking about the Holocaust—including my grandmother who lost 11 brothers and sisters in the camps,” says Greene, “So I never knew how to respond when people asked me how I reconciled my belief in a benign universe with what happened in Europe. How did those two things fit together?”

Greene’s search for an answer immersed him in Holocaust historiography. In 1995, he began production of a feature film based on interviews from the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimony at Yale University. The project required him to screen more than 300 hours of accounts by survivors, a three-year enterprise that resulted in “Witness: Voices from the Holocaust,” an awarding winning film that aired on PBS, and a companion book of the same title, published by Free Press. The job took its toll.

“Spending that much time screening witness testimony made me very intolerant of people around me, people absorbed in their petty lives and interests. How dare they party when this is what we’re capable of doing to one another? For perhaps six months I went into a depression. I couldn’t get on a subway without thinking of cattle cars or eat a sandwich without thinking of starvation. God forbid I should have to lift my arm to wave good-bye. That was a Nazi salute. Or give anyone my social security number—my SS number. Everything triggered thoughts of the Holocaust, and it drove me crazy. When I asked the people at Yale about it, they assured me it wasn’t so unusual. ‘Don’t worry. It’ll go away.’”

Greene found a way out of the depression. “My life is doubly blessed. I’ve been guided in my Holocaust study by gifted teachers at Yale, people like Professor Larry Langer and archivist Joanne Rudof. And I’ve been guided in my spiritual study by realized masters such as my guru Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. If you’re going to tackle life’s grand questions, there’s no substitute for that kind of mentorship.”

After “Witness” aired on PBS in 2000, hundreds of survivors contacted Greene to thank him for his work. Many approached him for help telling their stories. He politely declined. One call was from an elder woman living on the south shore of Long Island, not far from Greene’s home.

“My husband died a year ago,” Huschi Denson told him. “His last wish was that the truth about the Dachau trials be told.” Greene visited her Long Island home. In the basement, he found shelves sagging under the weight of tens of thousands of photos, trial transcripts, trial preparation notes and case studies on Nazi atrocities.

“At first, I thought, well, the Nuremberg trials are well documented. There’s no need for me to do anything more. But Huschi explained to me that Nuremberg involved Hitler’s policymakers, 22 men who never lifted their guns. At Dachau, south of Nuremberg, her late husband had been the chief prosecutor in trials of hundreds of murderers, the hands-on people who ran Hitler’s camps. The Dachau trials were the largest series of Nazi war crimes trials in history. But no one had ever heard of them. William Denson’s story was so dramatic and gripping, that I had to help,” says Greene.

The result was the book, Justice at Dachau, The Trials of An American Prosecutor and a documentary produced by Discovery Communications. “Bill Denson’s story helped me make connections between action and belief. He was a man of God who saw the Holocaust not a Jewish event but as a human event. His journey provided an important direction for my own search into human behavior and spirituality.”

Greene credits his parents with providing the impetus he needed to pursue a path to enlightenment. “My folks were divorced when I was very young,” he says, “but they both showed me love and filled me with the kind of Reform Jewish intellectualism that was at the forefront of many radical movements.”

In 1969, while studying comparative literature at the Sorbonne in Paris, Greene went to London during winter break and visited the Radha Krishna temple. At that time, the Krishna devotees were recording an album of Indian devotional music. When they learned that Greene played organ, he was invited to join them at Apple Studios where George Harrison, arguably at the peak of the Beatles’ unparalleled superstardom, was recording devotional music.

As Greene recalls, “We walked in the door—and there was George Harrison. After recovering from the initial shock of meeting one of my boyhood heroes, I said to myself, ‘If I stay here, I get both God and the Beatles? Okay, I’m in.’”

His holiday visit turned into 13 years of intense study and practice of bhakti or Hindu devotional yoga. “Bhakti is the mystic root of Hinduism. So the intellectual side of me was fulfilled. And the company couldn’t have been better—kind, funny, generous people with a sense of tikkun, or healing the world, doing good. Of course, the wardrobe was kind of funky, but in 1969, shaved heads, love beads, flowers, colorful clothing all fit right in. Except for the shaved head, I was doing the rest anyway,” laughs Greene. “So it wasn’t such a big change.”

His analytical mind discovered startling parallels between Judaism and Indian devotional culture. Love of learning, love of family, appreciation for the mysteries of life, and the pursuit of knowledge. As an added bonus, all Krishna food was strictly vegetarian and automatically Kosher.

Greene participated with other Krishna practitioners in a number of recording sessions with George Harrison. “We would always bring huge trays of vegetarian food,” Greene recalls, “and all kinds of people would show up at the studio to join us for lunch. Billy Preston, Donovan, Mary Hopkins, the other Beatles.”

In between sessions, he would go with his Krishna colleagues to Harrison’s home in Friar Park where Harrison had built a beautiful temple room. “I would play the harmonium, and we would chat, have lunch. George would play us new songs. He was very humble, unassuming, someone who was working hard to find a balance between his material success and spiritual happiness,” Greene recalls.

Harrison passed away two months after the twin towers fell. The two losses affected Greene. “I was about two miles away when the towers fell. Within an hour, people were walking by my office stunned, covered in white ash, like ghosts. I thought, ‘I’ve got to do something. Life is short!’”

Wanting to make a contribution in some way and to pass along what he’d learned about life’s spiritual dimension, he decided the best way would be to tell George Harrison’s story. In Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison (John Wiley & Sons) Greene tells the story of Harrison spiritual quest with intelligence, affection, objectivity, and a poetic flare. The book demystifies the mystical journey and humanizes the inner life of a music icon whose work and broader influence continue to affect spiritual seekers and music lovers alike. Greene reminds us that long before Band Aid, Farm Aid, Live Aid and so many other concerts, it was George who conceived the Concert for Bangladesh—the first charity concert in history and a direct outgrowth of Harrison’s belief in engaged spirituality.

In Harrison’s life story, Greene found a bridge between his academic background in Holocaust history and his personal background in enlightenment practices. “George understood that power can be used for good or evil,” he says. “While he chose to do his work behind the scenes—what peacemakers call Tier Two diplomacy—he was an advocate for positive change, first within ourselves, then within the larger world.

By linking justice to character, George captured a critical dimension of current international theory, namely that resolving conflict will not be achieved on political or military grounds but on spiritual grounds where deeper bonds can be forged. That’s quite an achievement for a pop superstar.”

Married and the father of two children, Greene sits on the Executive Council of the American Jewish Committee, Long Island chapter. He’s also Inter-religious Affairs Liaison to AJC National and a member of the Board of Advisers to the Holocaust Memorial and Educational Center of Nassau County. He has authored numerous articles that deal with justice and enlightenment and has spoken at hundreds of universities and law schools nationwide. He is a source for media on the subject of religion and war crimes tribunals and has been called upon to speak before such agencies at the Pentagon and The World Economic Forum.

“If there’s one thing I’ve learned on my own journey,” says Greene, "it’s that we have to do more than defend our own interests. To effect meaningful change we have to think broader.”

A man who believes in practicing what he preaches, Greene’s current project is a documentary on the legacy of Nuremberg for Touro Law School.